by Carol S. Hyman

Last holiday season, my daughter signed her father up for a service that emails him a question each week for a year, prompts that invite him to tell stories about his past. In addition to stock questions the service provides, other family members included in the loop can submit queries and all the answers will be collected at the end of the year in a book, a keepsake for future generations.

Most questions draw on his personal memory bank. What do you remember about your grandparents? What is the best vacation you took as a child? Some ask for preferences, like how do you like to travel? But an occasional prompt demands more contemplative consideration, as did this recent one: How have things changed since you were a child?

Those of us of a certain age could write a book on that subject, so narrowing the topic down is the first challenge. Patton, being a down-to-earth kind of guy, chose to focus mostly on tangible things, especially technological advances, like television, air conditioning, travel, communication. Reading his response, I realized that were I to answer that question, being more people oriented, I’d talk about social changes.

When I was a child in America in the Fifties, a feeling of confidence pervaded society. We’d won the war and entered a new era. Progress was America’s theme song. Polio was vanquished and a cure for cancer was right around the corner. Science was closing in on the mysteries of the universe and some even talked about the mysteries within us. I remember asking my mother what a Freudian slip was and, though the notion of unconscious motivations was puzzling, psychoanalysis offered the promise that even mental problems had solutions. Meanwhile, economic opportunities seemed boundless. The consensus, at least in my family, was that things weren’t bad and would only get better, as long as the Russians didn’t blow us up.

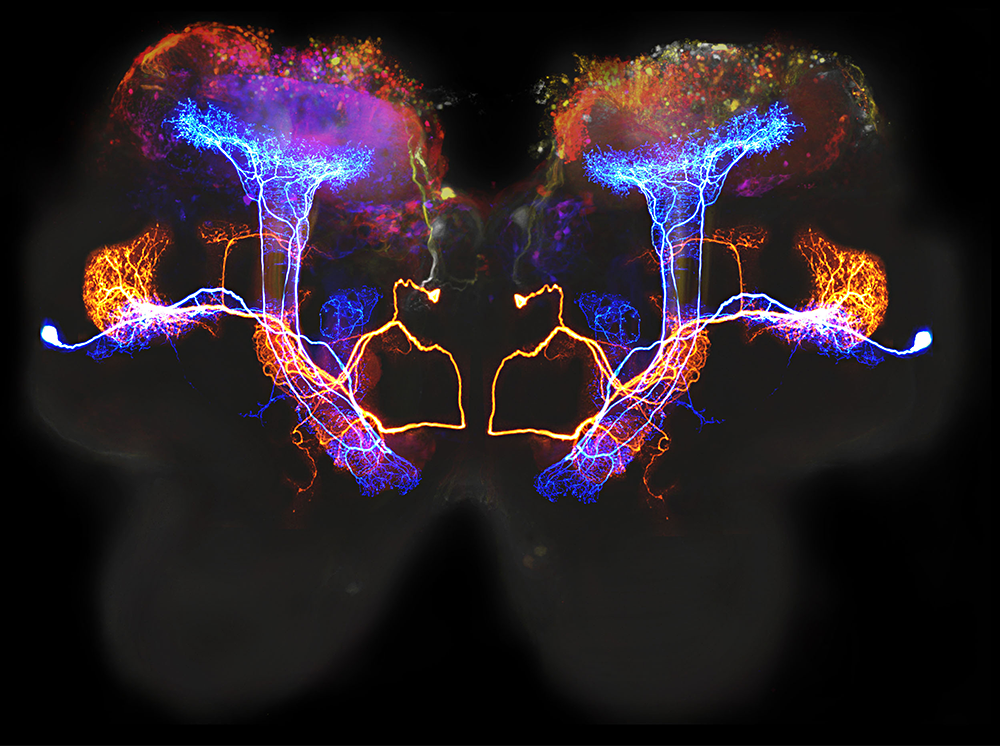

Or so I remember. But eyewitness reports are unreliable even when the observer has no agenda and in everyday life, we do have agendas. Plus unconscious influences are at work and, by definition, we don’t know what they’re up to. So memory generally confirms our current storyline. These days, that Fifties storyline can seem sweetly naïve. Or dangerously arrogant. Or willfully ignorant, or any number of other possibilities, depending on one’s storyline.

That’s the way it is with storylines. Comprising our deepest beliefs about ourselves and life, storylines provide the ongoing plots behind our inner running commentary. “It’s a dog-eat-dog world.” “No matter what I do, it’s never enough.” “The rich get richer.” “I can never get a break.” “The universe always gives you exactly what you need.” “Life is hard and then you die.” Without even noticing that we’re doing it, we filter and define experience to support those stories.

But if we’re willing to pay attention, the stories we tell ourselves about human society can evolve. Realizing how much damage was inflicted on people by rigid and biased views – about race, appropriate roles for genders, and sexual preferences, to name but a few – we’ve become more tolerant. But a social tectonic shift that moves a culture from separate drinking fountains for different races to gender neutral bathrooms in one lifetime not only destroys old forms, its aftershocks can shake the inner lives of the members of that society, and change the stories we tell ourselves.

Society starts with one-on-one interactions. To the extent that we’re ignorant of the storylines we’ve inherited and maintain, we’re powerless to determine whether they help bring about a better world or add to the confusion. But if we practice paying attention to our own mental contents, we can discern the storylines that shape our attitudes toward life and, in the process, create the space that allows us the freedom to shift toward more beneficial and collaborative perspectives and interactions.

Imagine our children in their dotage, being faced with the question, how have things changed since you were a child? Even now, books abound in which futurists predict extraordinary technological marvels, some of which will no doubt come to pass. The down-to-earth among our children might choose to focus on those, some of which may be out in space.

Now imagine the ones who’d choose to talk about society’s changes. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if they could report that we’d salvaged sanity – that people had become kinder, less likely to blame others for misfortune, and more willing to be responsible for bringing benefit into every situation? We’ll help create the conditions that will allow them to say that, if we learn to work with our own minds. And even without happily ever after, that story will still be a keepsake for future generations.

2 thoughts on “Story Time”

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this, Carol. Of course, that’s because I agree with you. :). So many golden nuggets. Best wishes with your Wednesday night group; I’ve just signed up for a harmony singing series on Wednesday nights. Alas.

Just wonderful how you teach us to look at our minds.